Falcons Flock to Urban Perches

Peregrines Trading in Wild Life for D.C. Area Roosts

By D'Vera Cohn

Washington Post Staff Writer

Saturday, April 15, 2006; A01

Stephanie R. Spears leaned over the side of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge with a video camera as the drawspan opened to let a construction barge pass through. Spears, an environmental specialist with the bridge replacement project, was looking for the pair of peregrine falcons nesting there when suddenly one of them came after her.

The shrieking bird with a sharp beak and hooked talons shot into the air, wheeled around and dived. "Watch your head!" Spears shouted to a handful of onlookers just as the female falcon veered away. Peregrines are said to be the fastest birds on Earth, capable of diving at 200 mph. This one was protecting three eggs.

The eggs are on a jumble of powdery road grit inside one of the bridge's concrete supports, only a few feet down from the rumble and shake of thousands of vehicles a day crossing between Maryland and Virginia. "It's an interesting place to make a nest," Spears said. "It's probably why she gets nervous when we stop traffic -- it's so quiet."

The Wilson Bridge is a dangerous place for a bird, but more of the region's peregrines are nesting on bridges, skyscrapers or other manmade structures than on the mountain cliffs that are their natural homes. Falcons are living on more than a dozen bridges in Maryland and Virginia and have made nests on tall buildings in Baltimore and Richmond.

The falcons' willingness to live near people and noise has let them thrive in an urban region. But it has frustrated state wildlife biologists who have tried in vain to get them to nest in the back country.

It is harder for a falcon to make a living on a mountain than in an urban area, said researcher Shawn Padgett. "They can't just take a plunge off a bridge and get a starling going by," he said. "They have to go out and hunt."

The Wilson Bridge peregrines, like the bald eagles that have a nest near the bridge, have an avid fan club. Paula Sullivan of Fairfax County visits Jones Point Park on the Alexandria shoreline several times a week to watch the peregrines through a spotting scope and to trade stories about them with people fishing there.

"The first time I saw the bird come in with prey, it really screamed -- I assume to announce its arrival," she said. "Feathers were flying in all directions. My assumption was that it was a pigeon. . . . It's really thrilling. I've gotten such an enormous kick out of it."

This is the second year that peregrine falcons have nested on the 55-foot-tall bridge. This year's eggs are due to hatch early next month. The birds laid eggs last year that vanished -- taken, Spears thinks, by raccoons.

Spears has seen raccoons walking the girders under the existing bridge and says they could use the span to traverse the Potomac -- just like humans. In many ways, the bridge is a miniature ecosystem of predators and prey. Pigeons and rats live there. Waterfowl linger under it, and gulls fly over it to scout for trash.

Construction workers on the bridge being built near the existing one have not found where the raccoons live, but they have learned to lock up their food after the creatures broke into their lunchboxes to eat their sandwiches. The raccoons have left their distinctive paw prints -- the front one resembling a human hand and the rear one a footprint -- in fresh concrete on the new bridge.

Life on the bridge meets the falcons' three basic needs: a rough surface with good drainage to lay their eggs, a high perch from which to hunt and a good food supply of other birds. The Wilson Bridge peregrines often sit atop 200-foot-tall construction cranes, even riding them as the cranes move along the Potomac River by barge. The falcons have made a noticeable dent in the bridge's pigeon population, but they also grab gulls and songbirds.

Once so rare that there were no breeding pairs east of the Mississippi, the peregrine falcon population has rebounded in the past three decades after the deadly pesticide DDT was banned. They were taken off the federal endangered species list in 1999.

Padgett said there are at least eight pairs making their home on bridges in Virginia and about the same number in Maryland, including on the Bay Bridge and a bridge off Baltimore Harbor. Padgett, a research associate at the Center for Conservation Biology at the College of William and Mary, plans to check a report of a pair of peregrine falcons on a highway bridge leading into the District from Virginia.

"Just looking at D.C., I can tell you there have to be more," he said. "We are looking for other pairs in the city."

But Padgett, whose center is deputized by the state to implement peregrine recovery efforts in Virginia, is concerned that more falcons are not nesting in the wild. So is Glenn D. Therres, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources associate director for wildlife.

In recent years, both states have removed baby falcons from nests on bridges and placed them in group nestboxes on mountain cliffs, where they are fed dead birds and have little interaction with people. The birds leave when they are able to fly on their own, and state officials hoped they would return when they were old enough to breed. The technique, called "hacking," has a proven track record.

Maryland has tried it for three years near Harpers Ferry, and although the first year's birds would be expected to return by now, none has. Virginia placed more than 60 birds in Shenandoah National Park in the past six years, and Padgett said only one pair returned to nest there, but others have been seen in urban areas.

"There's some art to this technique," said Therres, who has not given up on getting birds to live in the wild. "The theory is, you get birds acclimated to the cliff faces so they know to come back to them. But we really don't know when and at what age they actually imprint on the kind of habitat they should come back to."

Padgett said bridge life is perilous for baby falcons, which can easily drown or be killed in traffic when they try to fly. Most peregrine chicks die before they reach 6 months, he said. "It's definitely a bad setup," he said of the Wilson Bridge nest.

And although the odds for baby chicks also are bad in the mountains, Padgett said that is where falcons belong. He hopes that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which oversees the falcon population, will choose to remove the Wilson Bridge chicks from their current location and put them in a nestbox in Shenandoah National Park.

Sullivan, who has posted photos of the birds on her Web site, http://www.pbase.com/paulasullivan/peregrine_falcons , said she has mixed feelings about any attempt to remove the birds. "I'd love to see them have success where they are," she said. "I know there are experts who I trust to make the right decision. They seem so determined to do the best for the bird."

© 2006 The Washington Post Company

# posted by Unknown : 5:23 PM

# posted by Unknown : 3:35 PM

# posted by Unknown : 7:46 PM

My dad's Falcons on the way to an afteroon hunt

# posted by Unknown : 7:35 PM

# posted by Unknown : 7:35 PM

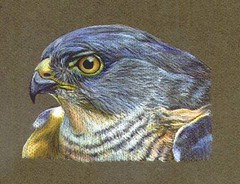

"Coloured pencil"

# posted by Unknown : 10:31 AM

# posted by Unknown : 10:30 AM

Ready to take wing

by Peter Rusland

The Pictorial

Apr 08 2006

Ed Harris, Ethan Hawke and Ronnie Hawkins aren't humans but they are local celebrities.

"Our three boys were bred here and they're the first babies fledged at Pacific Northwest Raptors," biologist Tina Hein says of the boisterous Harris hawks.

"Lots of them hatch but don't necessarily survive through fledgling, which is leaving the nest, flying and hunting on their own."

The trio of brothers was parent-reared by Queenie and Gollum after hatching in July.

They'll show off their young hunting skills during flying demonstrations this season at PNR.

"The time they would leave the nest naturally is when we started working with them," Hein says.

"We get them used to being with a person then we give them flying training introducing food.

"It's all about positive reinforcement. They hop a short distance to a piece of food and we increase that distance to what you'll see at a flying demonstration."

The hawks are trained raptors but remain "essentially wild with skills for the wild," she explains. "Most would survive in the wild if released. A lot of hunting is instinctive but with us they're honing their hunting skills every day.

"Birds are fed daily here but we do take them out hunting and they get some of that catch."

Hawks catch prey as large as themselves, "so Ed might catch a rabbit," Hein said.

PNR's breeding program prevents birds from having to be brought from outside B.C.

"It's about raptor education in general; how they live, hunt, and why they're important to the environment and spiritually. They're wonderful indicators of habitat pollution," she says. "These three brothers show our breeding program must be working and our program is about educating people."

Harris hawks are native to the American Southwest and range to Chile. "They're a wonderful educational tool because they're the only species of social raptors," Hein says. "They hunt in groups, but all other raptors hunt by themselves so we fly a pack of Harrises."

Hawks, eagles, and owls use their talons to kill prey.

During a flying demonstration they fly to a glove or a lure that looks like a rabbit or another bird.

"We show how a bird uses its aerial ability to catch prey."

Other species among 60 birds at PNR include red-tail hawks, eagles, owls and peregrine falcons all born in captivity.

Captive-bred birds are typically used for falconry.

"We do have some non-releasable, injured birds that are kept permanently that might otherwise possibly be euthanized," she says.

One of those recovering residents is Charlie, a one-wing bald eagle.

"Some are wild and non-releasable and a large majority are captive-bred flying birds and some are doing some breeding," Hein says of PNR, B.C.'s first bird-of-prey and falconry centre that opened in 2003.

"Our birds do in captivity what they do in the wild.

"They're the bosses; we work for them and they help us teach people about raptors."

PNR encourages folks to take injured birds found to a rehabilitation centre such as Errington's North Island Wildlife Recovery Centre.

"We're not a rehab centre, but we will take bird in an emergency; we don't want to see anything harmed," says Hein.

Doubleday Canada Limited

# posted by Unknown : 9:54 AM