The world is a mask that hides the real world.

Thatâs what everybody suspects, though the world we see wonât let us dwell on it long.

The world has ways - more masks - of getting our attention.

The suspicion sneaks in now and again, between the cracks of everyday existenceâ¦the bird song dips, rises, dips, trails off into blue sky silence before the note that would reveal the shape of a melody that, somehow, would tie everything together, on the verge of unmasking the hidden armature that frames this sky, this tree, this bird, this quivering green leaf, jewels in a crown.â¦

As the song dies, the secret withdraws.

The tree is a mask.

The sky is a mask.

The quivering green leaf is a mask.

The song is a mask.

The singing bird is a mask.

Friday, December 16, 2005

the falcon archetype's shiny mask & shadow

US deploys new top fighter jet

by Jim Wolf, Reuters, 16 December 2005

The futuristic F-22A "Raptor" fighter jet, designed to dominate the skies well into the 21st century, joined the U.S. combat fleet on Thursday, 20 years after it was conceived to fight Soviet MiGs over Europe.

The Air Force said "initial operational capability" had been achieved at the 1st Fighter Wing's 27th Fighter Squadron at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia.

Pilots in the squadron, the Air Force's oldest in continuous operation, have been training on the F-22, the Air Force's most advanced weapon system, for about a year.

"If we go to war tomorrow, the Raptor will go with us," Gen. Ronald Keys, head of the Air Force's Air Combat command, said in a statement. He said an initial group of 12 was ready for combat worldwide or for homeland defense.

The squadron may swing through the Pacific next year, probably flying from Guam and elsewhere, though no decision has been made about where to best "showcase" it, Keys said in a later teleconference with reporters.

With the Soviet Union gone, defense analysts have cast the F-22 as the weapon of choice for any future U.S. conflict with China, for instance over Taiwan.

"There is a clear role for F-22 here," said Daniel Goure, a former Pentagon strategist now at the Lexington Institute, an Arlington, Virginia, research group with close ties to the U.S. defense establishment.

The aircraft's role is to "kick the doors down" in a conflict, as Pentagon officials put it, knocking out defenses on the ground and in the air to clear the way for other warplanes and forces.

The radar-evading Raptor is twice as reliable and three times more effective than the F-15C Eagle it is replacing as the top U.S. air-to-air fighter, according to Lockheed Martin Corp., its developer.

"It's a fighter pilot's dream," said former F-15 pilot Col. Walter Givhan, lauding the plane's integrated avionics, stealth and speed. Givhan is wing commander at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, where the latest round of F-22 testing was completed.

Lockheed described the fighter as the world's most advanced and said it was "relevant for the next 40 years."

Boeing Co. and Northrop Grumman Corp. are top F-22 subcontractors. United Technologies Corp.'s Pratt & Whitney unit makes the aircraft's two engines.

STEALTHY AND SUPERSONIC

The Raptor combines low-observability, or stealth, with supersonic speed, agility and cockpit displays designed to boost greatly pilots' awareness of the situation around them.

At a "fly-away" cost of about $130 million each for the most recent batch, not including research and development, it is also one of the most controversial U.S. warplanes ever.

Critics have termed it unaffordable overkill in a world without the potential threat of a Soviet Union able to send swarms of MiGs into a dogfight, which prompted its inception in 1986.

The Air Force is planning to stretch F-22 production until 2010 to keep Lockheed's production line open pending arrival of its more affordable F-35 Joint Strike Fighter family of aircraft that will also go to the Navy, the Marines and co-developing nations that include Britain, Italy and Turkey.

The F-22 also has a ground attack capability to drop 250-pound (113.5-kg), small-diameter bombs or 1,000-pound (454-kg) Joint Direct Attack Munitions while flying at supersonic speeds.

Gen. Michael Moseley, the Air Force chief of staff, has said the F-22 is needed against threats such as Russian-built surface-to-air missiles sold overseas.

Moseley said on Tuesday he hoped to buy 183 F-22s, four more than currently in the budget and enough for seven combat-ready squadrons, down from the 750 F-22s once planned.

Final assembly has been completed on 67 of the 107 F-22s already purchased by the Air Force, Lockheed's program manager, Larry Lawson, said in a statement.

Copyright © 2005 Reuters Limited. All rights reserved.

street dreams of future flight past

IMG_8089: African Pygmy Falcon

Thursday, December 15, 2005

hungry ants show teamwork

origin of army ants' cooperative behavior

EurekAlert! Public release date: 15-Dec-2005

Scientific insights come at the darnedest times.

Animal behaviorist Sean O'Donnell was having an afternoon cup of coffee when a giant earthworm exploded out of the leaf litter covering the jungle floor in an Ecuadorean nature preserve. The worm, later measured at nearly 16 inches long, was pursued by a column of hundreds of raiding army ants that quickly paralyzed or killed it.

That sighting, and another involving what turned out to be the same species of army ant feeding on the carcass of a snake, has led O'Donnell of the University of Washington and several colleagues to offer a new theory on the origin of cooperative hunting behavior in army ants, which are among the most socially complex animals known.

Writing in the current issue of the journal Biotropica, O'Donnell and biologists Michael Kaspari of the University of Oklahoma and John Lattke of Universidad Central de Venezuela, propose that mass cooperative food foraging, a key element in the behavior of army ants, may have begun as a way to subdue large prey.

The species that O'Donnell observed is called Cheliomyrmex andicola and it lives mainly underground in New World tropical rainforests. It had been previously identified, but little was known about its behavior or prey until the two chance encounters at the Tiputini Biodiversity Station, an ecological preserve in eastern Ecuador.

The ants are brick red in color and their size would be considered medium or large when compared to most common ant species found in United States. What makes Cheliomyrmex such a fearsome predator is that its workers have claw-shaped jaws that are armed with long, spine-like teeth. These teeth may serve to help Cheliomyrmex workers attach themselves to their prey's skin during attack

O'Donnell, who was bitten and stung when he collected Cheliomyrmex specimens, said the ants' stings were particularly painful and itchy, comparable to the stings of fire ants. He and his colleagues believe the venom in a Cheliomyrmex sting is toxic and/or paralytic, considering how quickly the giant earthworm became immobile after being attacked.

The researchers said the species is apparently unique among New World army ants in removing and consuming vertebrate flesh, based on the observation of the ants feeding on the dead snake. They noted that raiding parties of other New World army ants occasionally sting and kill small vertebrates such as lizards, snakes and birds, but do usually not consume them. Other New World army ants prey heavily on insects and other invertebrates.

O'Donnell said Cheliomyrmex is related to Old World driver ants in Africa, which also have large-toothed jaws and feed on large-bodied prey. The ancestor of Cheliomyrmex may have split from Old World army ants as long as 105 million years ago, at around the time when Africa and South America separated during the breakup of the giant continent Gondwana.

"Cheliomyrmex may be telling us that cooperative hunting of large prey is an evolutionary predecessor of going after smaller prey," said O'Donnell. "Typically, army ants follow a lifestyle of attacking other social insect colonies. But Cheliomyrmex is not following this lifestyle."

The discovery of Cheliomyrmex 's predation was part of a larger project to sample the number of army ant species and their activity at four New World tropical rainforest sites in Costa Rica, Panama, Venezuela and Ecuador. The research was funded by the National Geographic Society.

For more information, contact O'Donnell at 206-543-2315 or sodonnel@u.washington.edu

Contact: Joel Schwarz

joels@u.washington.edu

206-543-2580

University of Washington

A front view of the army ant Cheliomyrmex, showing its fearsome jaw and teeth. [photo: Michael Kaspari, U of Oklahoma]

if wings had ears

Thursday Dec 15, 2005

by MELISSA CALHOUN, Ohio University Office of Research Communications

Bat wings show a series of raised domes with touch receptors. [photo: John Zook]

ATHENS, Ohio -- Bats have an “ear” for flying in the dark because of a remarkable auditory talent that allows them to determine their physical environment by listening to echoes. But an Ohio University neurobiology professor says bats have a “feel” for it, too.

John Zook’s studies of bat flight suggest that touch-sensitive receptors on bats’ wings help them maintain altitude and catch insects in midair. His preliminary findings, presented at the recent Society for Neuroscience meeting, revive part of a long-forgotten theory that bats use their sense of touch for nighttime navigation and hunting.

The theory that bats fly by feel was first proposed in the 1780s by French biologist Georges Cuvier, but faded in the 1930s when researchers discovered echolocation, a kind of biological sonar found in bats, dolphins and a few other animals. Bats use echolocation to identify and navigate their environment by emitting calls and listening to the echoes that return from various objects.

Zook believes the touch-sensitive receptors on bats’ wings work in conjunction with echolocation to make bats better, more accurate nocturnal hunters. Echolocation helps bats detect their surroundings, while the touch-sensitive receptors help them maintain their flight path and snag their prey.

Touch receptors take the form of tiny bumps, or raised domes, along the surface of bats’ wings. The domes contain Merkel cells, a type of “touch” cell common in bumps on the skin of most mammals, including humans. Bat touch domes are different, however, because they feature a tiny hair poking out of the center.

When Zook recorded the electrical activity of the Merkel cells, he found they were sensitive to air flowing across the wing. These cells were most active when airflow – particularly turbulent airflow – stimulates the hair. When a bat’s wing isn’t properly angled or curved during flight, air passing next to the wing can become turbulent. Merkel cells help bats stay aerodynamically sound by alerting them when their wing position or curve is incorrect, preventing the creatures from stalling in midair.

“It’s like a sail or a plane. When you change the curve of a wing a little bit, you get improved lift. But if you curve it too much, the bat – or plane – may suddenly lose lift, hitting a stall point and falling out of the air. These receptor cells give bats constant feedback about their wing positions,” said Zook, who has studied bats for more than 30 years, focusing on echolocation and the bat auditory system. The bat’s sense of touch has been a side interest since the early 1980s.

To test his hypothesis, Zook removed the delicate hairs from bats’ wings with a hair removal cream. Then he let them fly. The bats appeared to fly normally when following a straight path, but when they’d try to take a sharp turn, such as at the corner of a room, they would drop or even jump in altitude, sometimes erratically. When the hairs grew back, the bats resumed making turns normally.

“It was obvious they had trouble maintaining elevation on a turn,” he said. “Without the hairs, the bats were increasing the curve of their wings too much or not enough.”

The bats’ flight behavior also changed based on the area of the wing where the hairs were removed. For example, when Zook removed hairs along the trailing edge of the wings and on the membrane between the legs, the bats were able to fly and turn effectively, but they tended to pitch forward because they couldn’t control their in-flight balance.

Zook’s research also points to the importance of a second type of receptor cell in the membranous part of bats’ wings. Nerve recordings revealed that these receptors respond when the membrane stretches. Zook calls areas on the wing where these stretch-sensitive cells overlap “sweet spots” because they are where bats like to snag their prey. In the lab, Zook shot mealworms covered with flour into the air and recorded how the bats caught them. He could tell from the flour imprints on the wings that the bats caught their prey almost exclusively in the stretch-sensitive sweet spots.

Copyright © 2005 Ohio University. All Rights Reserved.

Contact: John Zook, (740) 593-2269, zookj@ohio.edu

Media Contact: Andrea Gibson (740) 597-2166, gibsona@ohio.edu

medicated owl meditates on season's joys?

Owl discovered in Christmas tree found with marijuana in system

Posted: 12/15/2005 11:24 am

Last Updated: 12/15/2005 11:36 am

Sarasota, FL - Here's a holiday story you just won't believe.

A family found an owl in their Christmas tree, and the bird apparently had a little hooter in him.

A small screech owl was found in a live Christmas tree that a family bought.

They kept the tree for five days before they decided to decorate it.

When they did, they found the owl.

Animal control officers came to get the owl, and when they did, they made a shocking discovery!

"I kept smelling him and smelling him, saying 'What is that odor'. It was lying there as happy as can be,"says one animal control officer who was at the scene.

"Curiously enough, the owl's feathers smelled very, very potently like marijuana," says Animal Control Officer Dering. They examined the owl, looked at its eyes, big owl eyes, and the owl was, in the vernacular, stoned."

Blood tests confirmed the owl was flying high, on marijuana.

They checked him out, fed him and named him Cheech.

He'll be released in a few days.

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

"Each person has a reindeer guardian angel"

Mr. Vitebsky's happiest pages are devoted to the reindeer, the harsh beauty of the taiga and the intimate bond between the Eveny and their animals. Each person has a reindeer guardian angel, and on the trail, wrapped in multiple layers of reindeer-skin clothing, the herders look a little like reindeer themselves. Reindeer hair, which is hollow and traps body heat, has nearly magical insulating powers, which is a good thing, because a herder who leaves his tent without a coat on can freeze to death in minutes....from: A Home in the Arctic, Where the Reindeer Still Roam

by William Grimes, New York Times, 14 December 2005

Monday, December 12, 2005

narwhal's tusk is a sensory organ

It's Sensitive. Really.

By WILLIAM J. BROAD, New York Times, December 13, 2005

For centuries, the tusk of the narwhal has fascinated and baffled.

Narwhal tusks, up to nine feet long, were sold as unicorn horns in ages past, often for many times their weight in gold since they were said to possess magic powers. In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth received a tusk valued at £10,000 - the cost of a castle. Austrian lore holds that Kaiser Karl the Fifth paid off a large national debt with two tusks. In Vienna, the Hapsburgs had one made into a scepter heavy with diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds.

Scientists have long tried to explain why a stocky whale that lives in arctic waters, feeding on cod and other creatures that flourish amid the pack ice, should wield such a long tusk. The theories about how the narwhal uses the tusk have included breaking ice, spearing fish, piercing ships, transmitting sound, shedding excess body heat, poking the seabed for food, wooing females, defending baby narwhals and establishing dominance in social hierarchies.

But a team of scientists from Harvard and the National Institute of Standards and Technology has now made a startling discovery: the tusk, it turns out, forms a sensory organ of exceptional size and sensitivity, making the living appendage one of the planet's most remarkable, and one that in some ways outdoes its own mythology.

The find came when the team turned an electron microscope on the tusk's material and found new subtleties of dental anatomy. The close-ups showed that 10 million nerve endings tunnel from the tusk's core toward its outer surface, communicating with the outside world. The scientists say the nerves can detect subtle changes of temperature, pressure, particle gradients and probably much else, giving the animal unique insights.

"This whale is intent on understanding its environment," said Martin T. Nweeia, the team's leader and a clinical instructor at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine. Contrary to common views, he said, "The tusk is not about guys duking it out with sticks and swords."

Today in San Diego, Dr. Nweeia is presenting the team's findings at the 16th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, sponsored by the Society for Marine Mammalogy.

James G. Mead, curator of marine mammals at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, where Dr. Nweeia is a research associate, said the exposed nerve endings appear to be unparalleled in nature.

"As far as I can see, it's a unique thing," Dr. Mead said in an interview. "It's something new. It just goes to show just how little we know about whales and dolphins."

He noted that no theory about the tusk's function ever envisioned its use as a sensory organ.

In the Canadian wilds, the team recently conducted a field study on a captured narwhal, fitting electrodes on its head. Changes in salinity around the animal's tusk, Dr. Nweeia found, produced signs of altered brain waves, giving preliminary support to the sensor hypothesis. The unharmed whale was then released.

With the basics now in hand, the team is working to understand how the narwhal uses the information. One theory is that the tusk can detect salinity gradients that tell if ice is freezing, a hazard that has killed hundreds of narwhals. Tusk readings may also help the whales track environments that favor their preferred foods.

"It's the kind of discovery," said Dr. Mead of the Smithsonian, "that opens up a lot of other questions."

Little about the narwhal's appearance or behavior offers clues to the tusk's sensory importance. The whale has eyes, though small ones. It also has a thick layer of blubber and no dorsal fin so it can swim easily under the ice. Like any whale, it must surface periodically to breathe air. And as in dolphins, its mouth is set in a permanent smile.

The word narwhal (pronounced NAR-wall or NAR-way-l) is said to derive from old Norse for "corpse whale," apparently because the animal's mottled, splotchy coloring recalled the grayish, blotched color of drowned sailors.

Though shy of humans, the animals are quite social. They often travel in groups of 20 or 30 and form herds of up to 1,000 during migrations.

Males weigh up to 1.5 tons, grow about 15 feet long and are conspicuous by their tusks, which can grow from six to nine feet in length. A few females have tusks and, in rare cases, narwhals can wield two of the long teeth. Though often ramrod strait, the tusks always grow in tight spirals that, from the animal's point of view, turn counterclockwise.

The long ivory tusk "looks like a cross between a corkscrew and a jousting lance," Fred Bruemmer, an Arctic explorer, wrote in "The Narwhal" (Swan Hill Press, 1993).

Narwhals live mainly in the icy channels of northern Canada and northwestern Greenland, but they are found eastward as far as Siberia.

The whale's close cousin, the snowy white beluga, thrives in captivity. The shy narwhal tends to die.

Arctic explorers have often observed them at a distance because narwhals frequently raise their heads above the water, their tusks held high. Jens Rosing, in his book "The Unicorn of the Arctic Sea" (Penumbra Press, 1999), tells of seeing them during expeditions off Greenland. There the whales would frolic and apparently mate.

"Over a hundred can be seen at once," he wrote. "They often rise vertically out of the water, lifting themselves with strong movements of their tail fin so that half their body is above water."

Mr. Rosing added: "There is great confusion of movement - both females and males take part. Often one can see a male and female shoot up from the water, trembling, belly to belly."

When luxuriating on their backs in the water, narwhals often turn their heads so their tusks point straight up. Dr. Nweeia of Harvard said the Inuit, the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, who know the narwhal intimately, have a name for the whale that translates as "the one that is good at curving itself to the sky."

Around A.D. 1000, the narwhal tusk debuted in history as a profitable lie. Historians say people in the far north learned of narwhals from Norsemen or perhaps from finding animal bodies occasionally washed up on northern shores. It is known that the Vikings hunted the narwhal and acquired tusks from Arctic natives.

Unscrupulous traders passed them off as one of the most prized objects of all time: unicorn horns.

The ancient Chinese, Greeks, Romans and other peoples had accepted the unicorn as real, and the arrival of the beautifully spiraled objects seemed to prove the animal's existence. The supposed horns sparked huge interest because they were said to have the power to cure ills and neutralize poisons.

Kings and emperors, eager to foil assassins, had cups and eating utensils made of the precious horns. A London doctor advertised a drink made from powdered tusks that could cure scurvy, ulcers, dropsy, gout, consumption, coughs, heart palpitations, fainting, rickets and melancholy.

The horns became an icon of power, both earthly and divine, in part because of their religious associations. In medieval times, the unicorn was seen as a symbol of great purity and of Christ, the motif common in religious art. The fantastic beast appeared in many thousands of images, Mr. Bruemmer wrote, and "All carry a horn that is unmistakably a narwhal tusk, the only long, spiraled horn in all creation."

Churches put small pieces of "unicorn horn" in holy water, giving ailing commoners hope of miracle cures. Meanwhile, the bishops of Vienna carried staffs made of the precious ivory, while St. Mark's Basilica in Venice displayed a horn wreathed in purple velvet.

By the 17th century, the deception began to falter amid the expansion of New World exploration and multiplying reports of bizarre whales that bore long tusks. Ole Wurm, a Danish zoologist, investigated the matter and in 1638 exposed the horn's true origins in a public lecture.

As the unicorn myth died a slow death, the reputation of the narwhal grew larger than life. Explorers claimed its tusk could punch holes in thick ice, and that males battled with their long tusks for supremacy. In 1870, Jules Verne told how a narwhal could pierce ships "clean through as easily as a drill pierces a barrel."

Dr. Nweeia, a general dentist in Sharon, Conn., with an interest in dental anthropology, developed a taste for exotic investigations while doing research on Indian tribes in the Amazon and children in Micronesia. He lectured on how animal and human teeth differ, and eight years ago he began to wonder about narwhals and their odd tusks.

"They defied most of the principles and properties of teeth," he recalled. Many narwhal reports proved contradictory, he found, and "my interest spiraled like the tooth."

In 2000, Dr. Nweeia decided to investigate the animal closely and first trekked to its icy habitat in 2002, going to Pond Inlet, a tiny settlement at the northern tip of Baffin Island. There he met David Angnatsiak, an Inuit guide who agreed to help. Under international agreement, the Inuits are allowed to hunt narwhals, which they eat and harvest for their tusks.

During expeditions in 2003 and 2004, aided by the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Dr. Nweeia was able to gather head and tusk specimens, which he brought back for analysis. He and his colleagues tracked a clear nerve connection between the animal's brain and tusk, finding the long tooth heavily enervated. But why it should be so remained a mystery.

The investigators zeroed in on the riddle with sophisticated instruments at the Paffenbarger Research Center of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, a federal organization in Gaithersburg, Md. The American Dental Association finances the research center.

Rough deposits of calcified algae and plankton coated the outside of the tusks Dr. Nweeia brought back. The scientists decided to remove them in an acid bath to get down to the surface of the tooth before viewing it under an electron microscope. First, however, they decided to give the uncleaned tusk a cursory microscopic examination.

It was a shock. There, contrary to all known precepts of tooth anatomy, they found open tubules leading down through the mazelike coating to the tooth's inner nerves and pulp.

"That surprised us," recalled Frederick C. Eichmiller, director of the Paffenbarger Research Center. "Tubules in healthy teeth never go to the surface."

Extrapolating from a count of open tubules over one part of the tooth's surface, the team estimated that the average narwhal tusk had millions of openings that led down to inner nerves.

"No one knew that they were connecting to the outside environment," Dr. Nweeia said. "To find that was extraordinary."

His collaborators include Naomi Eidelman and Anthony A. Giuseppetti of the Paffenbarger Research Center, Yeon-Gil Jung of Changwon National University in South Korea and Yu Zhang of New York University.

Increasingly, the investigation centers on how the whales use their newly observed powers. One central unanswered question is how sensory abilities in males might relate to herd behavior and survival.

The scientists, noting that the males often hold their tusks high in the air, wonder if the long teeth might sometimes serve as sophisticated weather stations, letting the animals sense changes in temperature and barometric pressure that would tell of the arrival of cold fronts and the likelihood that open ice channels might soon freeze up.

Dr. Nweeia noted that the discovery does not eliminate some early theories of the whale's behavior. Tusks acting as sophisticated sensors, he said, may still play a role in mating rituals or determining male hierarchies.

He added that the nerve endings, in addition to other readings, undoubtedly produce tactile sensations when the tusk is rubbed or touched, and that these might be interpreted as pleasurable.

This tactile sense might explain why narwhals engage in what is known as "tusking," where two males gently rub tusks together, Dr. Nweeia said. He added that the Inuit seldom report aggressive contact, undermining ideas of ritualized battle.

Dr. Nweeia said that gentle tusking might also be a way that males remove encrustations on their tusks so tubules stay open, allowing them to better function as sensors. "It may simply be their way of cleaning or brushing teeth," he said.

He called the basic discovery mind boggling, especially given the freezing temperatures of the Arctic.

"This is one of the last places you'd expect to find such a thing," Dr. Nweeia said of the large sensory organs. "Cold is one of the things that tubules are most sensitive to," as people sometimes discover when diseased gums of human teeth expose the tubules.

"Of all the places you'd think you'd want to do the most to insulate yourself from that outside environment," he said, "this guy has gone out of his way to open himself up to it."

Copyright 2005The New York Times Company

x marks a species facing extinction

Groups rally to safeguard hundreds of imperiled species

Safeguarding 595 sites around the world would help stave off an imminent global extinction crisis, according to new research published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (www.pnas.org).

Conducted by scientists working with the 52 member organizations of the Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE –– www.zeroextinction.org), the study identifies 794 species threatened with imminent extinction, each of which is in need of urgent conservation action at a single remaining site on Earth.

The study found that just one-third of the sites are known to have legal protection, and most are surrounded by human population densities that are approximately three times the global average. Conserving these 595 sites should be an urgent global priority involving everyone from national governments to local communities, the study's authors state.

Th United States ranks among the ten countries with the most sites. These include Torrey Pines in California, a cave in West Virginia, a pond in Mississippi, and six sites in Hawaii. The whooping crane and the recently rediscovered ivory-billed woodpecker are two spectacular American species that qualify for inclusion. Particular concentrations of sites are also found in the Andes of South America, in Brazil's Atlantic Forests, throughout the Caribbean, and in Madagascar.

"Although saving sites and species is vitally important in itself, this is about much more," said Mike Parr, Secretary of AZE. "At stake are the future genetic diversity of Earth's ecosystems, the global ecotourism economy worth billions of dollars per year, and the incalculable benefit of clean water from hundreds of key watersheds. This is a one-shot deal for the human race," he added. "We have a moral obligation to act. The science is in, and we are almost out of time."

"We now know where the emergencies are: the species that will be tomorrow's dodos unless we act quickly," said Taylor Ricketts, lead author of the study. "The good news is we still have time to protect them."

Among the 794 imperiled mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and conifers are monkey-faced bats, cloud rats, golden moles, poison frogs, exotic parrots and hummingbirds, a hamster and a dormouse, a penguin, crocodiles, iguanas, monkeys, and a rhinoceros. Among the most intriguingly-named are: the Bloody Bay poison frog, the volcano rabbit, the Ruo River screeching frog, the Bramble Cay mosaic-tailed rat, the marvelous spatuletail (a hummingbird), and the Sulu bleeding-heart (a dove).

While extinction is a natural process, the authors note that current human-caused rates of species loss are 100-1,000 times greater than natural rates. In recent history, most species extinctions have occurred on isolated islands following the introduction of invasive predators such as cats and rats. This study shows that the extinction crisis has now expanded to become a full-blown assault on Earth's major land masses, with the majority of at-risk sites and species now found on continental mountains and in lowland areas.

Also published today are a site map and a report that details the actions required to save these sites and species. These items, along with a searchable database of sites, web links and media contacts for the Alliance's 52 member organizations, and photos of AZE sites and species for media use, can be found at: www.zeroextinction.org/press.htm.

EurekAlert! Public release date: 12-Dec-2005

Contact: Tom Lalley

tom.lalley@wwfus.org

202-778-9544

World Wildlife Fund

L and Manuka

be nice to bees, they recognize human faces

Adrian G. Dyer1,2,*, Christa Neumeyer1 and Lars Chittka3

1 Institut fur Zoologie III (Neurobiologie), Johannes Gutenberg Universität, Mainz, 55099, Germany,

2 Clinical Vision Sciences, La Trobe University, Victoria 3086, Australia

3 School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary, University of London, London, E1 4NS, UK

* Author for correspondence at present address: Department of Plant Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB2 3EA, UK (e-mail: a.dyer@latrobe.edu.au)

Accepted 13 October 2005

Recognising individuals using facial cues is an important ability. There is evidence that the mammalian brain may have specialised neural circuitry for face recognition tasks, although some recent work questions these findings. Thus, to understand if recognising human faces does require species-specific neural processing, it is important to know if non-human animals might be able to solve this difficult spatial task. Honeybees (Apis mellifera) were tested to evaluate whether an animal with no evolutionary history for discriminating between humanoid faces may be able to learn this task. Using differential conditioning, individual bees were trained to visit target face stimuli and to avoid similar distractor stimuli from a standard face recognition test used in human psychology. Performance was evaluated in non-rewarded trials and bees discriminated the target face from a similar distractor with greater than 80% accuracy. When novel distractors were used, bees also demonstrated a high level of choices for the target face, indicating an ability for face recognition. When the stimuli were rotated by 180° there was a large drop in performance, indicating a possible disruption to configural type visual processing.

Key words: visual processing, face recognition, honeybee, brain

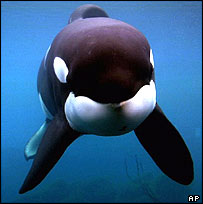

sad orca discovery

Arctic orcas highly contaminated

By Paddy Clark, BBC News, 12 December 2005

Killer whales have become the most contaminated mammals in the Arctic, new research indicates.

Norwegian scientists have found that killer whales - or orcas, as they are sometimes known - have overtaken polar bears at the head of the toxic table.

No other arctic mammals have ingested such a high concentration of hazardous man-made chemicals.

The Norwegian Polar Institute tested blubber samples taken from creatures in Tysfjord in the Norwegian Arctic.

The chemicals they found included pesticides, flame retardants and PCBs - which used to be used in many industrial processes.

Chemical sink

Animals at the top of the food chain are particularly affected, and whales - like polar bears - can reflect the health of the marine environment.

The researchers are particularly worried about the flame retardants, because unlike many other harmful chemicals, some are still legal.

The international environmental group, WWF, says the Arctic has become a chemical sink.

It says the findings dramatically underline the need for European Union ministers to decide on strong legislation when they meet this week.

However, WWF says it fears pressure from the chemicals industry could lead to any new laws being so watered down that they will protect neither the environment nor human health.

Story from BBC NEWS:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/science/nature/4520104.stm

Published: 2005/12/12 02:19:05 GMT

© BBC MMV

Sunday, December 11, 2005

like a bird

Prairie Falcon Launch

superior surgery success

Sunday, December 11, 2005

Perrysburg, Ohio - Superior,a 6-month-old peregrine falcon,underwent surgery Saturday at the Perrysburg Animal Hospital to fix his broken left wing,said Mona Rutger, director of the Back to the Wild Wildlife Rehabilitation& Nature Center near Castilia, Ohio.

Veterinarians inserted two vertical pins into the falcon's humus bone, which extends from the shoulder to the elbow, then attached a Kirchner apparatus,which will hold the pinned bone in place, Rutger said.

"We were worried because peregrines typically stop breathing during surgery because of the anesthetic,but he came through fine," she said.

Superior will have his wing wrap removed in three days,then undergo therapy to keep his shoulder joint mobile. He will live in a small conditioning cagefor about 2 1 / 2 weeks before being moved to a large flight cage,Rutger said.

Superior could be released in early spring if he shows good flight, she said.

To find out more about the center,go to its Web site:

www.backtothewild.com

© 2005 The Plain Dealer © 2005 cleveland.com All Rights Reserved.