The world is a mask that hides the real world.

Thatâs what everybody suspects, though the world we see wonât let us dwell on it long.

The world has ways - more masks - of getting our attention.

The suspicion sneaks in now and again, between the cracks of everyday existenceâ¦the bird song dips, rises, dips, trails off into blue sky silence before the note that would reveal the shape of a melody that, somehow, would tie everything together, on the verge of unmasking the hidden armature that frames this sky, this tree, this bird, this quivering green leaf, jewels in a crown.â¦

As the song dies, the secret withdraws.

The tree is a mask.

The sky is a mask.

The quivering green leaf is a mask.

The song is a mask.

The singing bird is a mask.

Saturday, April 30, 2005

the wild parrots of Telegraph Hill

The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill

Difficult to believe this photo was taken in St. Hubert not really that very many – perhaps 75 – years ago.

Beautiful birds, but as a faithful Congregant I can't see birds in the city and not wonder what diseases they might be carrying, we've known for decades that the Enemy will use them to transmit biological agents....ever since West Nile: birds get the bug, mosquitos bite the birds, mosquitos transfuse the virus into their human victims....although, strangely, now I feel this research somehow pulling me away from ChurchØne® and a lifetime of indoctrination (I started to type "education" but the archives make it easy to spot the propaganda, those patterns recur again and again), in a way I can't even define, but the realities of ChurchØne® don't seem so real any more, the contradictions are poking out. Learning so much that I never suspected – nobody does – makes me question and doubt everything that I have been taught. Alienated for most of my adult life, and only now, it seems, do I begin to appreciate root causes....

The photo reminds me of a passage from an author I've discovered in the archive (his works seem to have been systematically excluded from public view; he began publishing in the late 1950s and continued until well into the 21st century), Thomas Pynchon, an amazing writer whose depictions of paranoia strike a sympathetic chord these days, from his 1990 novel Vineland [12]:

Up and down that street, she remembered, television screens had flickered silent blue in the darkness. Strange loud birds, not of the neighborhood, were attracted, some content to perch in the palm trees, keeping silence and an eye out for the rats who lived in the fronds, others flying by close to windows, seeking an angle to sit and view the picture from. When the commercials came on, the birds, with voices otherworldly pure, would sing back at them, sometimes even when none were on.

the passion of conviction

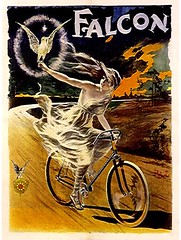

A curious rant, but falcons and falconry tended to attract cranks and crackpots, I had learned in the years of my research.

I'll admit it: I'm hooked.

What next?

today's harvest

urban birds

Friday, April 29, 2005

consciousness based on sound

Mystery Interlocutor's comments hung in the air like a film of gauze, filtering the light to a pool of pale yellow on my cluttered desk. For the moment, I chose to ignore them, plunging back into the server bank I've been exploring these past few days.

Whales seem to have gotten caught up in the same censorship press with falcons, but there it is, publications about whale communications and intelligence drop off as dramatically as any having to do with raptors, and it's part of a general decline of activity related to animal intelligence or consciousness. Everybody knows the significance of stopping the teaching of evolution in schools around the turn of the 20th century; the notion that humans and animals have more in common than not is just silly. Ask any Congregant. Obviously, animals are God's creatures, too, but God gave men dominion over Creation. After all, who eats whom? Does the horse ride the man?

It's difficult not to speculate what might have happened if people like those described in the two articles [71] below hadn't been "reassigned," if ChurchØne® Elders had invested less in genetic engineering and more in consciousness and communications research, if we had continued to push closer to understanding nonhumans instead of seeking to exploit them?

Unweaving the song of whales

by Molly Bentley, BBC News

For nearly a decade, Cornell University researcher Christopher Clark has been eavesdropping on the ocean, hoping to decipher the enigmatic songs of whales.

Using old US Navy hydrophones once employed to track submarines, he has collected thousands of acoustical tracks of singing blue, fin, humpback and minke whales.

His bioacoustics lab is now able to pinpoint the location of individual singers, and determine the length of their song. As a result, he's had to redraw the map of whale acoustics.

"The range is enormous," explained Dr Clark. "They have voices that span an entire ocean."

Drawing on newly declassified acoustic data from the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS), and using new tools that can crunch high volumes of them, Dr Clark has determined that whales' songs travel over thousands of kilometres and also that increasing noise pollution in the oceans impedes the animals' ability to communicate.

Booming voices

It is not certain whether whales thousands of kilometres apart communicate directly with each other, or what their messages contain. But the results support a 30-year theory that, before the advent of modern shipping, the animals' booming voices would have resounded from one ocean basin to another.

With sound that is loud and low, in other words, "beautifully designed" for long distance travel, the singing of a whale in the waters off Puerto Rico could carry 2,600km to the shores of Newfoundland, says Dr Clark.

When scientists create a digital map of the sound as it propagates in the water, it "illuminates the entire ocean", he adds.

The pan-oceanic range is fitting for massive 30-190-tonne creatures that rely on reflected sound, rather than light, to navigate.

"You are dealing with animals that are highly acoustically oriented," said Dr Clark. "Their consciousness and sense of self is based on sound, not sight."

Dr Clark and other whale researchers spoke at the recent annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington DC about how new technologies are revealing whale secrets at the same time that human activity continues to threaten their well-being.

He is particularly concerned with noise pollution, or "acoustic smog". Noise from shipping vessels doubled every decade, said Dr Clark, which means a whale's world decreases by a factor of two.

Over 20 years, its 1,600km acoustic radius shrinks to 400 km, and, presumably, limits the range over which animals can navigate and find food or mates.

"We are slowly, inexorably, raising the tide of ambient noise so that their worlds are shrinking just to the point where they're dysfunctional," Dr Clark believes.

Military Sonar

He distinguishes between the chronic noise from ships and the acute bursts of noise from military sonar, which recent evidence suggests startles the animals and leads to decompression sickness or stranding.

Despite the ban on commercial fishing, other menaces besides noise pollution, such as commercial fishing nets and ocean contaminants also continue to threaten the health of whale populations, according to Roger Payne, president of the conservation group Ocean Alliance.

His team is in the final year of a five-year expedition designed to establish the first baseline levels of synthetic pollutants in the ocean. Long-lived industrial pesticides, such as DDT and PCBs, re-concentrate as they move up the marine food chain. Whales are at the top of that chain.

"Insect repellents and insecticides which have been spread on fields on land have now gotten out to whales in mid-ocean," said Dr Payne.

His ship, the Odyssey, and its crew have travelled across the Pacific Ocean taking tissue samples of sperm whales, whose longevity allow plenty of time for chemicals to accumulate in their fatty tissue. They have collected 1,100 tissue samples so far, and have run preliminary analysis on 30 of them.

"We find these substances present in every single one of those samples," explained Dr Payne, who adds he will test all the samples once the voyage is complete.

"Toxic dumps"

The study will be the first global measure of pollution in a single species at the top of aquatic food chain, although high levels of pollutants in marine animals have been detected in previous studies.

PCB toxicity is defined as 50 parts of contaminant per million parts of animal, (50 milligrams per kilo) tests have revealed up to 400 ppm in killer whales, 3,200 in beluga whales and 6,800 in bottlenose dolphins.

It makes the animals "swimming toxic dump sites," according to Dr Payne.

Contaminants such as PCBs and DDT have been shown to inhibit a mammal's immune system, its ability to function, and the development of its young.

"The young receive roughly the contaminant concentration that their mother has, add to it what they get in their food during their lifetime, and then pass that double dose to their offspring," said Dr Payne.

He is also concerned about the possibility of what he calls "double stressors," in which seemingly weak threats to an animal are combined and create a one-two punch that causes serious harm, even death.

He cited a 2003 University of Pittsburgh study in which bullfrog tadpoles had little reaction to pesticides and to the smell of predators when exposed to them in separate experiments. When the stressors were combined, mortality rose to 80-90%.

Biologists had yet to determine whether such synergistic effects apply to other vertebrates, such as whales, said Dr Payne, who suggests that a combination of acute noise, contaminants or predation, could serve as double stressors.

While some whale populations are recovering since the 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling, anthropogenic influence may play a decisive role with populations that are at critical levels and endangered, such as the Northern right whale.

Specialised ecosystems

When whales are threatened, so are the specialised ecosystems that depend on them - and on their carcasses.

New research into whale falls - the sinking of whale carcasses to the ocean bottom - is revealing a weird and diverse assortment of creatures; some not found anywhere else in the ocean.

A whale fall is such a rare find that scientists like University of Hawaii oceanographer Craig Smith have made a practice of towing dead beached whales to sea and sinking them themselves.

"It's really a community service," said Dr Smith. "A rotting beached whale is a big, stinking mess."

Then they watch to see who shows up. A whale fall provides an organic smorgasbord - up to two million grams of carbon in its blubber and oily bones - for a host of creatures, some of which may be so specialised, they rely on dead whales to complete their lifecycle.

First scavengers such as hagfish appear and eat the soft tissue. Then bacteria and invertebrates devour the skeleton. Chemoautotrophs - including bone-eating zombie worms - gather when the bones begin to emit sulphide. At this stage, whale falls provide parallels to the sulphide-loving ecosystems at hydrothermal vents.

Scientists speculate that creatures that require sulphide may use whale falls as sulphide stepping stones - to disperse to new hydrothermal vent communities - and may even have a spot in the evolutionary lineage of some of the vent species, according to Dr Smith.

"It's quite possible that the ancestors of the giant tube worms on vents were actually animals that were living on dead whales," he says.

Bone-eating zombie worms

Evidence from DNA sequencing techniques also suggests that, not only may whale falls host more species than thrive at hydrothermal vents, some have highly specialised adaptations.

The bone-eating zombie worms, for example, use internal bacteria to break down the fats in the whalebone and appear to be unique to whale falls.

"It is increasingly evident that there are major kinds of habitats, major types of organisms with extreme evolutionary novelty that remain to be discovered," said Dr Smith.

But as the whales disappear, so do these exotic ecosystems.

By some estimates, large whale populations have been reduced by 75% as a consequence of whaling. Following conservation biology theory, said Dr Smith, a 75% drop in one population meant that 30-40% of the species that depend on it would go extinct.

"We are beginning to appreciate what whaling may have done to these specialised communities," explained Dr Smith. "And it's very likely that there either have been or - may be on-going - species extinctions on the deep sea floor connected with whaling.

Sonata for Humans, Birds and Humpback Whales

by Natalie Anger, New York Times

When humanity's ancestors discovered, a million years or so ago, the exquisite pleasure of a hot meal by the fire, they might very well have set the mood with a little night music — a shimmering cadenza played on a slender bone flute, perhaps, or a hymn to the spirits belted out a cappella.

As researchers conclude in the current issue of the journal Science, the love of music, that unslakable, unshakable, indescribable desire to sing and rejoice, rattle and roll, is not only a universal feature of the human species, found in every society known to anthropology, but is also deeply embedded in multiple structures of the human brain, and is far more ancient than previously suspected.

In fact, what could be called the "music instinct" long antedates the human race, and may be as widespread in nature as is a taste for bright colors, musky perfumes and flamboyant courtship displays.

In twin articles that discuss the flourishing field of biomusicology — the study of the biological basis for the creation and appreciation of music — researchers present various strings of evidence to show that music-making is at once a primal human enterprise, and an art form with virtuoso performers throughout the animal kingdom.

The researchers discuss recent discoveries in France and Slovenia of musical instruments dating back to 53,000 years ago — more than twice the age of the famed Lascaux cave paintings or the palm-size "Venus" figurines. The instruments are flutes carved of animal bone, and are so sophisticated in their design as to suggest that humans had already been fashioning musical instruments for hundreds of thousands of years. And when Jelle Atema of the Marine Biology Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass., an author on one of the new reports and an accomplished flutist who studied with the renowned Jean- Pierre Rampal, reconstructed his own versions of the archaic flutes from bits of ancient bone and gave them a blow, he and his collaborators were impressed by their sweetness and versatility.

"What you immediately hear when he plays these flutes is the beauty of their sound," said Patricia M. Gray, the lead author on the first of the two Science articles. "They make pure and rather haunting sounds in very specific scales.

"It didn't have to be this way," she added. "They could have sounded like duck calls." Dr. Gray, a professional keyboardist, is the artistic director of the National Musical Arts, the ensemble-in-residence at the National Academy of Sciences, and the head of the academy's Biomusic program, a group of scientists and musicians who, according to their mission statement, "explore the role of music in all living things."

The new reports also emphasize that humans hold no copyright on sonic brilliance, and that a number of nonhuman animals produce what can rightly be called music, rather than random drills, trills and cacophony. Recent in-depth analyses of the songs sung by birds and humpback whales show that, even when their vocal apparatus would allow them to do otherwise, the animals converge on the same acoustic and aesthetic choices and abide by the same laws of song composition as those preferred by human musicians, and human ears, everywhere.

For example, male humpback whales, who spend six months of each year doing little else but singing, use rhythms similar to those found in human music, and musical phrases of similar length — a few seconds. Whales are capable of vocalizing over a range of at least seven octaves, yet they tend to proceed through a song in stepwise lilting musical intervals, rather than careering madly from octave to octave; in other words, they sing in key. They mix percussive and pure tones in a ratio consonant with that heard in much Western symphonic music. They also follow a favorite device of human songsters, the so- called A-B-A form, in which a theme is stated, then elaborated on, and then returned to in slightly modified form.

Perhaps most impressive, humpback songs contain refrains that rhyme. "This suggests that whales use rhyme in the same way we do: as a mnemonic device to help them remember complex material," the researchers write. "It's very easy to play along with pure, unedited whale songs," said Dr. Gray, who has written movements for saxophone, piano and whale. "They're absolutely comprehensible to us."

Birds, too, compose songs with the same notes, rhythmic variations, harmonic patterns and pitch relationships as those found in human compositions. The hermit thrush, for example, considered one of the lushest of avian vocalists, sings in the so- called pentatonic scale, in which the octaves are divided into five notes. "This is a very recognizable and very pleasant scale that is found across many human cultures," Dr. Gray said. "The pentatonic scale is the scale on which the prehistoric flutes are built, and it's also the basis for a lot of rock 'n' roll music today." Birds of a feather, it seems, rock together.

The California marsh wren may sing as many as 120 themes in a given jam session, with each theme matched by its immediate neighbor in what is known among musicians as the call-response pattern. Some birds even use instruments: the palm cockatoo of Northern Australia selects a hollow log of a preferred resonance, and then breaks off a twig to use as a drumstick.

"Music is far, far older than our species," said Roger Payne, president of the Ocean Alliance in Lincoln, Mass., and a co-author on one of the papers. "It is tens of millions of years old, and the fact that animals as wildly divergent as whales, humans and birds come out with similar laws for what they compose suggests to me that there are a finite number of musical sounds that will entertain the vertebrate brain."

Neuroscientists have just begun getting a handle on how the brain perceives and appreciates music, and the results are as yet confusing and somewhat contradictory. On the one hand, Dr. Isabelle Peretz of the University of Montreal and her colleagues have studied patients with lesions in the auditory cortex that impair only their ability to recognize music, while leaving unscathed their power to understand speech, environmental sounds and other acoustic information.

Dr. Peretz's results suggest that the brain has something specifically designed to process music, although the precise location or nature of such a do-re-mi keeper remains unknown.

On the other hand, Dr. Mark Jude Tramo, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School, argues in the second Science paper that neuroimaging studies of people performing or listening to music have failed to find a "music center" in the brain devoted strictly to music cognition.

All of the neural structures that participate in the musical experience, he argues, are players in other forms of cognition, auditory and otherwise. For example, Dr. Tramo says, a region called the left planum temporale, which is critical for perfect pitch, is also involved in language processing. And though the right hemisphere of the brain traditionally has been considered the "music hemisphere," recent neuroimaging studies from his and other laboratories reveal a more subtle interplay between the left and right halves of the brain in the course of a musical experience.

The left hemisphere seems particularly important for so-called "fast acoustic" processing, which would tell a listener whether, say, a note was being bowed on a violin or plucked on a guitar. The right hemisphere takes over in "slow acoustic" processing, appreciating the notes following that initial "attack." At which point, if all goes well, the brain cedes control to the body, and the party begins.

heresy?

The challenge confronted me on the antique palm-top screen.

"OK," I replied. "Why would ChurchØne® be concerned to keep this document a secret? Blasphemous content, for starters. The references to eagles being eaten alone would get it banned. And, it's safe to assume the scholar is a follower of the evolution heresy. More than enough reasons to re-groove just about anybody, seems to me."

That's good as far as it goes, wrote Mystery Interlocutor. But, go back to this passage:

"....many archaeologists think that the birds of prey were brought into the settlements for religious reasons, independently of the carcasses of other species which were part of the food supply.

But we can gain extra clues from an examination of the different kinds of birds of prey found among the remains. A first analysis seems to indicate a serious flaw in the hypothesis that birds of prey were used for hunting: the majority of the bones belong to the larger birds of prey, such as eagles, buzzards, vultures and eagle owl, while falcons are much less common.

The problem is that most of the larger birds of prey are unsuitable for hunting – at least, according to purists in the world of falconry."

He can't see it. He can see part of it. The birds of prey - all of them - are there for religious reasons.

Falcon remains are rare in these ancient settlements because the falcon was the deity. The other birds of prey were brought in to worship and serve as sacrifices offered by the people to the falcon deity.

There won't be as many falcon remains at these sites because these people weren't sacrificing falcons, they were worshipping falcons, feeding falcons the bloody and still-quivering organs of the larger raptors that in nature would prey on the falcon. They probably released the falcons into the wild after their temple service, let the peregrines return to their peregrinations, the way that falconers have always done with birds of passage trapped for a season of hunting then release back into the wild...

We know from the archeological remains that the falcon is established as a deity in Egyptian religion from the earliest period, indicating uncounted pre-historic ages in which falcon spirituality and ritual would have evolved prior to the written record.

But that's not the picture this article is slanted to support. This author suggests that larger raptors - eagles, vultures - were the object of worship, dominant at a time when the relatively fewer traces of the falcon appear at these sites.

I thought about that for a minute.

"The servers I've catalogued contain all kinds of stuff about falcons and falconry, all the way back to ancient Egypt – that stuff's no secret," I thumbed. "Every school kid knows the story of the Hebrews and ancient Egypt in the story of Christianity's rise and ChurchØne®'s consolidation of power under Christ's Eagle in the spread of the Congregation throughout the Western Hemisphere (Americas: North, South, Central). Any competition between falcon and eagle was over centuries ago, by the time Christ was born. Falcon's just another bird with a history."

You've read about the remains of eagles used as food 12,000 years ago? Published in some format available to the public?"

"No. But, I haven't been looking for that kind of material, either."

OK. I figured you'd take some persuading. I'll get back to you.

Before I could thumb, "Why me?" the screen scrambled again.

falconer devastated by falcon theft, death

UPDATE: Grommet was found dead later during the day that the story (below) was published. Magnificent bird. R.I.P.

Grommet [Sacramento Bee]

Purloined falcon is owner's passion

By Christina Jewett

Sacramento Bee, 29 April 2005

Douglas Bell knew his peregrine falcon might soar over ranchers' fields in Yolo County and never return. Still, he released the bird, Grommet, to hunt last summer, only to discover Wednesday that the falcon had fallen prey to a thief in Bell's east Sacramento backyard.

Bell, a professor of biology at California State University, Sacramento, is now consumed by his search for the 6-year-old raptor, and concern for his welfare.

Aside from a hand-fed diet of pigeon and quail, falcons need special care, Bell said.

"Otherwise, you could traumatize them mentally," he said.

Sacramento Police spokeswoman Michelle Lazark said Thursday that a burglary detective will be assigned to the case. Bell describes the purloined bird as stocky and crow-sized, blue-black with a cream-rust torso, with a squeak like a rusty door hinge.

Bell said he went through a detailed process five years ago to obtain a permit for the endangered bird, which was raised by falcons in the Bay Area.

"It takes such a commitment," Bell said. "I feed him on my fist on the glove every day. I spend time with him to make him happy."

Bell has shown Grommet, a well-mannered bird, to his conservation and ornithology classes at CSUS, he said.

"(Students) love to see a live creature," he said.

Bell said he's studied the peregrine falcon since 1970, when birds populated only five of 100 California cliffs known as nesting sights. Now, the birds have bounced back, with about 350 adults in the state, he said.

"(Grommet) is a guide for me that tells me what wild birds are, in a sense, thinking," he said. "By living with a falcon, you develop a more intimate rapport with what wild birds are doing."

On hunting trips, Bell said, he takes Grommet to open fields where the bird flies out of sight, and returns to stalk the starlings and pigeons that Bell rouses from the fields.

"As a falconer, one accepts the fact that you have a probability of losing (the bird), or having some other raptor kill it. What's unacceptable is when a human comes along and takes him," Bell said.

Bell arrived home at 64th Street near Elvas Avenue to find Grommet's mews (the proper name for a falcon shed) broken into on Wednesday. He said the padlock had apparently been pried open with a crowbar.

"I was ... quite upset, largely because this is probably the worst thing to happen, to have the bird stolen by someone who doesn't know how to care for it," he said.

Bell said cooked meat or beef could be hazardous to Grommet's health, and his talons could be hazardous to his captor.

"If he's grabbed, he will try to defend himself," Bell said.

Bell posted fliers in his neighborhood on Thursday and said he's offering a $1,000 reward for anyone who provides information that leads to Grommet's safe return. He encourages anyone who has the bird to surrender him to city police, CSUS police or the CSUS biology department.

The Sacramento Police Department can be reached at (916) 433-0650. Bell can be reached at the CSUS biology department at (916) 278-6535 or dbell @csus.edu.

objets d'art

Sailing

streetbird

Thursday, April 28, 2005

human nature

falconry in the last Ice Age

Why do you suppose ChurchØne® would want to keep this secret?

SCPBRG Research Note 04.14.2005.9 [archive I.D. suppressed]

The earliest falconers must have taken part in sacred sacrifice rituals at holy temple sites. From heaven falcon brings enlightenment - both the metaphorical light of understanding and the evanescent but altogether physical rays of the morning sun - thus to heaven bloody falcon returns the ritual sacrifice of whitest dove symbolizing the spirit received.

The scholar, below, doesn't mention this possibility, but consider the spectacle of a falconer who, dressed in all his finery and accoutrements of his art, looses a falcon which soars impossibly high in the sky, stoops at terrifying speed, kills the white dove prey several tens of tense seconds after its release - surely fit for a special memorial ceremony or other holy occasion.

The article [63] is a bit long but well worth reading if you have a few moments to spare:

A new theory pushes the origins of falconry deep into prehistory, perhaps to the end of the last Ice Age around 12,000-10,000 years ago. It may even have been one of the first steps for humans on the road to agriculture.

Falconry has long been regarded as a noble sport, and it has a very ancient pedigree. According to traditional views, people first began to use tame birds of prey for hunting game in central Asia during the first or second millennium BC. Through trade and other contacts, the practice then extended westwards into the Middle East, and eventually to Europe.

But that theory raises a major puzzle. The first artistic views of falconry come not from the Far East, but from Turkey. Several carvings from around 1500 BC show a large bird on the fist of a human figure. Grasped in the same fist is the figure of a hare (presumably the quarry) held by the back legs.

Another, somewhat later, example has been found in northern Iraq. Dated to the period of King Sargon II (722-705 BC), this bas-relief depicts a small bird of prey on the wrist of a man. Significantly, this carving seems to show ‘jesses’ (leather thongs used to secure the bird to the human fist), tied to the bird’s feet and passing between the thumb and forefinger of the falconer. If so, it may indicate that falconry (and its paraphernalia) was well developed by the eighth century BC in the Middle East.

In both cases, some researchers have interpreted these carvings as purely religious or symbolic scenes. But if these examples do indeed depict hawking, then the sport is at least 3,500 years old in Western Eurasia.

New meat on old bones

Archaeological excavations are now throwing an exciting new light on the origin of falconry in the Middle East, along with new clues to the reasons why – and when – it began. The name of the game is zooarchaeology - the study of the bones of fossil mammals and birds.

In recent years, archaeologists have excavated many early human settlements in Israel, Jordan, Syria, Iraq and Iran which date back to 8000-10,000 BC. Among the remains, they have consistently uncovered the bones of birds of prey. Most researchers interpret these bones as remnants of food left by the humans living at those sites, or as elements of religious activities.

But could there be an alternative explanation? For example, these fragile remains might represent the earliest management and training of living birds of prey - and the possible first faltering steps towards falconry. (The term ‘falconry,’ incidentally, is used to cover all trained birds of prey, not just the birds known as falcons.)

In order to explore this idea further, we need to put these finds into perspective. That means:

* understanding the significance of other animal bones from these early sites

* exploring the historical records of falconry, and the current practices of peoples who still hunt with birds of prey

* placing these data within the environmental and cultural context of the world as it was ten millennia ago.

Late Stone Age diet

Remains from these early sites have surprised archaeologists by revealing the inhabitants exploited a broad and diverse range of mammals and birds. It marks a major shift in human diet. Earlier in the Stone Age, people tended to hunt mainly the larger mammals. But during the short period of human history from 12,000 to 10,000 years ago, the economic focus of hunting in the Middle East appears to shift from large mammal species towards a broader range of food – most importantly, a greater reliance on smaller animals.

The range of mammals and birds remains at all these sites is very similar. They include gazelle, fox and hare, as well as game birds such as partridges, francolins and sandgrouse. Hunters must have been both skilled and versatile in order to catch enough of these small species to feed their settlement. They certainly used a variety of techniques to capture their prey, including trapping, netting, digging and perhaps even poisoning.

Perhaps the birds of prey found at these sites were also part of the repertoire of hunting techniques - an additional means of catching smaller prey species. In other words, was falconry first developed and employed as one of the hunting strategies in the Middle East as early as the late Stone Age?

Which birds were used?

Although we find bones of predator birds and prey species in the same deposits, this doesn’t prove that these birds were used to hunt the prey. As mentioned above, many archaeologists think that the birds of prey were brought into the settlements for religious reasons, independently of the carcasses of other species which were part of the food supply.

But we can gain extra clues from an examination of the different kinds of birds of prey found among the remains. A first analysis seems to indicate a serious flaw in the hypothesis that birds of prey were used for hunting: the majority of the bones belong to the larger birds of prey, such as eagles, buzzards, vultures and eagle owl, while falcons are much less common.

The problem is that most of the larger birds of prey are unsuitable for hunting – at least, according to purists in the world of falconry. The smaller eagles and some buzzards are mainly scavengers and carrion feeders, and will only occasionally hunt live prey. Other large species, like the vulture, can easily be trained to fly to the hand but apparently cannot be made to kill anything. Falconers today generally use a relatively select range of species, all at the smaller end of the size range. These include the larger bird-killing falcons (such as the peregrine, the lanner, the saker and sometimes the gyrfalcon) and the majority of goshawks and sparrow-hawks – precisely the kinds of bird that are rare in the Middle Eastern archaeological sites.

But can we be sure that ancient falconers followed the same practice? All birds of prey can be easily tamed and trained, and present-day falconers in Central Asia, India, and even Europe have trained a whole host of larger birds of prey to fly and hunt, some more successfully than others.

Golden eagles, for example, can be trained to catch something as large and formidable as a wolf. In Uzbekistan, and Khazakstan today, some skilled hunters still depend upon golden eagles to catch hares, foxes and wolves for their skins, which are then sold.Various travellers in Central Asia have described the use of eagles for hunting large quarry. In the thirteenth century, Marco Polo participated in a hunt using eagles with the great Kublai Khan and commented: "He has also a great multitude of eagles which are very well trained to hunt; for they take wolves and foxes and buck and roe deer, hares and other small animals."

In 1559, the European traveller A. Jenkinson reported seeing Tartars using "Haukes" (probably golden eagles) to hunt wild horses and states that "they are used to bewilder the hunted animal." Lieutenant D. Carruthers in 1949 described natives of Tarim using eagles to bring wild pig to bay, so the hunters can close in and club the victim to death. In these cases the eagle has little more than nuisance value, but it's sufficient to confuse the quarry in order to bring it to bay and bag.

Of particular significance are the comments of Aelian (circa. AD 220), supposedly quoting ‘Ctesias the Cnydian.’ Ctesias was court doctor to the Persian King Artexeises II (Mnemnon) in the early fifth century BC. His early treatise on falconry describes the country and customs of the ‘pygmies’, a mysterious people inhabiting some part of Central Asia. He states that "they hunt hares and foxes with crows, yellow-breasted marten cats and with cornices and eagles." (Other translations suggest crows, kites, rooks and eagles were used).

Ctesias also provides details of how these unlikely species were trained to catch hares and foxes. "They catch young eagles and also the young of ravens and vultures, bring them up and train them for hunting. The procedure is as follows. They hang meat on a tame hare or a tamed fox and let it run; then they send the birds after them and permit them to take hold of the meat. The birds try this with all their might, and when they have caught up with the one or the other, they may take the meat as a prize and this for them is a great lure. When they have been brought to precision in this type of hunting, the Indians let them loose on mountain hares and wild foxes. In hope of the usual meal, they chase after the prey which appears, and catch it very quickly."

This description helps to solve another problem for the falconry hypothesis – the presence of vulture remains at these early sites. By their very nature, vultures in the wild are carrion feeders and do not hunt and kill live prey. However, if the remarkable evidence from Ctesias can be believed, vultures appear to have been trained to catch hares and foxes in the fifth century BC.

Vultures can certainly be easily tamed and trained to fly to hand, particularly the Egyptian vulture, which is flown today at several bird of prey centres around Britain. Even if the vultures at these sites weren’t actually used for hunting, falconers may have used them to train smaller birds of prey to hunt the larger ones, a common practice described in the historic literature.

Eagle-owl bones at many of the Stone Age sites add another interesting dimension to the falconry hypothesis. This extremely powerful bird of prey can also be trained to hunt a range of prey, and eagle owls are particularly effective at dusk or even at night. A small group of falconers today use the eagle owl in this way. A Persian treatise on falconry (the Baznama-Yi Nasiri, translated by Lt Col. E. S. Harcourt and Lt Col. D. C. Phillott in 1868) states that "what the golden eagle is to the day, the eagle owl is to the night. Hares and foxes fall an easy prey to it."

Others have described how hunters can use eagle owls - along with other owl species - to lure other large birds of prey to the ground, where they can be captured or killed. This method works very well, particularly if the owl is left disabled or tethered on the ground, where it is invariably attacked and mobbed by other birds of prey.

Falconry and religion

Several researchers have offered a religious or symbolic explanation for the presence of the numerous bird-of-prey remains at the later prehistoric sites of the Near and Middle East. The idea is supported by the ritualistic importance attached by many cultures in historical times to birds of prey - perhaps the most famous being the Plains Indians of North America, with their large eagle-feather head-dresses. In the vast majority of cases, they practise cultural or religious rituals where wild birds of prey are captured and killed.

Recent evidence from the Kirghiz of Central Asia shows that falconry has played a major role in their religious beliefs. The Kirghiz believed the eagle to be the ancestor of the shaman - the priest who used magic to heal the sick and control the future. Because shamans were believed to be the first hunters, all hunters were also considered to be saints. When a pregnant woman experienced difficulty in childbirth, shamans thought an evil spirit caused her suffering. A strong brave berkhut (tame golden eagle) was brought to her bedside, since the evil spirits were thought to be afraid of its eyes. The killing of a fox by the berkhut was also perceived to be a symbol of fertility.

The hunt itself was also subject to set rituals: "the night before the hunt, the berkutcheu [eagle falconer] washes himself, abstains from any sexual involvement or alcohol and the berkhut is fed only white meat washed to rid it of blood".

So it is quite possible that falconry (the management and training of live birds of prey) may have served a dual spiritual and utilitarian role at these early sites.

Falconry, foraging and farming

How can a study of the antiquity of falconry possibly contribute to our understanding of human society and culture in the late Stone Age, as the last Ice Age drew to a close?

This was the period when human groups in the Near and Middle East underwent a radical change in their economic and social life. Archaeological remains testify to one of the most significant events in human history - the shift from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering wild resources to a settled one of farming with the first domestication of crops and livestock. This momentous event led inextricably to a rapid rise in human population, the subsequent emergence of the first major civilisations and a radical re-shaping of the world as we know it.

The sites we’ve been discussing in the Near and Middle East provide significant insights into this transition. The remains contain such a wide range of species that it seems the inhabitants were facing a rapid decline in their food resources - perhaps because they were over-exploiting a hunting territory that was forever diminishing. This is certainly a plausible explanation for these hunters apparently shifting towards smaller, less rewarding, species. It was perhaps the driving force that funnelled many of these groups down the road towards agriculture as their only alternative survival strategy.

Eating smaller species must have meant changes in the way that people hunted them down – and using birds of prey might have been one solution. What’s most intriguing is that this period coincides with the appearance of the domestic dog. Descended from tamed wolves, the dog may have served as a hunting aid and companion. Thus the origins of falconry, developed as an additional hunting strategy (with possible spiritual or religious dimensions), may be linked with the domestication of the dog.

If the bird-of-prey remains at these sites do indeed represent evidence of experimentation with their taming and management, then birds of prey may take their place (along with the dog) as the earliest domestic animals. More important, both must have been extremely influential in setting the scene for the subsequent domestication of the later economically important species - sheep, goat, cattle and pigs.

On the basis of all the available evidence, the significance of bird-of-prey bones recovered from these early sites remains very much open to debate. Whether they simply represent domestic food refuse, symbolic artefacts or the remains of tamed and managed birds, is still far from clear. The idea that birds of prey were domesticated before the advent of agriculture, and may have even contributed to its beginnings, may still be a theory – worthy of further, more critical consideration – but it potentially offers crucial insights into our origins.

Copyright (c) FirstScience.com

Dr. Keith [name witheld] is a research fellow in the Environmental Archaeology Unit, University of [name witheld]. He specialises in the study of animal and human bones from archaeological sites. His major areas of research include the origins of domestication and ancient DNA.

Think about it.

Check you later.

Scrambled screen.

I clicked open the document and read it again, carefully.

chance

Jean (Hans) Arp. Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance. 1916–17. Torn-and-pasted papers on gray paper, 19 1/8 x 13 5/8" (48.6 x 34.6 cm). Purchase. © 2002 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

This elegantly composed collage of torn-and-pasted paper is a playful, almost syncopated composition in which uneven squares seem to dance within the space. As the title suggests, it was created not by the artist's design, but by chance. In 1915 Arp began to develop a method of making collages by dropping pieces of torn paper on the floor and arranging them on a piece of paper more or less the way they had fallen. He did this in order to create a work that was free of human intervention and closer to nature. The incorporation of chance operations was a way of removing the artist's will from the creative act, much as his earlier, more severely geometric collages had substituted a paper cutter for scissors, so as to divorce his work from "the life of the hand."

The screen scrambled, then:

"Are you willing to take a chance, Redactor?"

I don't know, I answered.

Do you have any idea where that picture and description come from?

No.

Never heard of MOMA?

Museum of Modern Art, in New York City. That was demolished in 2004, to make room for a ChurchØne® tabernacle. But I don't recall that image from the database. The database was taken off-line not long after that, if I remember my ChurchØne® history, along with the rest of the non-Christian art.

What if it wasn't?

What if it wasn't what?

Demolished. Or taken off-line.

That stopped me. What could this person be talking about?

You've got my attention.

Wednesday, April 27, 2005

Silence or inhuman void?

As I watched, it buzzed and vibrated gently but distinctly. I stared at it as it buzzed, goggle-eyed, I imagine, if anybody was watching.

The following quote materialized on the screen:

"Soon silence will have passed into legend. Man has turned his back on silence. Day after day he invents machines and devices that increase noise and distract humanity from the essence of life, contemplation, meditation.... Tooting, howling, screeching, booming, crashing, whistling, grinding, and trilling bolster his ego. His anxiety subsides. His inhuman void spreads monstrously like a gray vegetation."

Next, the attribution, presented as a hyperlink:

Jean Arp

I couldn't resist.

Click.

a boy & his falcon

Thomas the Falconer (Sokoliar Tomáš)

directed by Václav Vorlícek, Slovak Republic, PG, 2000, 96 mins, children's story

The main hero of this tale is 14 year-old Thomas, who has the gift of understanding animal speech. He lives with his family in the mountains, until the tragic death of his father.

In order to fend for his family, he sets off for the mighty Balador's castle. It's there that he befriends Balador's daughter. However, a chain of events at the castle gets him involved in a course of intrigue, which he has to battle against. While on the run, he meets the falconer Vagan, and he takes refuge at his lodge in the mountains. Will Thomas' gift help him gain the legendary royal falcon? Will the falcon help him fight for justice and his own freedom?

the Moorpark mammoth

MOORPARK, Calif. - The remarkably well-preserved remnants of an estimated half-million-year-old mammoth — including both tusks — were discovered at a new housing development in Southern California.

An onsite paleontologist found the remains, which include 50 percent to 70 percent of the Ice Age creature, as crews cleared away hillsides to prepare for building, Mayor Pro Tem Clint Harper said.

Paleontologist Mark Roeder estimated the mammoth was about 12 feet tall, Harper said. Roeder believed it was not a pygmy or imperial mammoth, but he had not yet determined its exact type, Harper said.

"It's considered a very significant find, and it's a very complete fossil. It's unusual because it was found all the way down near the bedrock," Harper said. "We asked if carbon dating could be used and they said no way, it's too old."

Harper said the first bones were spotted several days ago and a special crew was called in after Roeder found more remnants, including the 6- and 7-foot-long tusks.

"They've been encased in plaster and burlap and removed from the site," Harper said.

Moorpark in Ventura County is about 30 miles west-northwest of downtown Los Angeles.

"The Moorpark mammoth, that's what we'll call it," Harper said.

Other Ice Age creatures have been found in recent years around Southern California, including a mastodon in Simi Valley, a mammoth in Oceanside and a pygmy mammoth on the Channel Islands. [62]

beneath the street: the jungle

kakapo care

It's a Jungle Out There!

From the BBC:

Rare parrot receives special care

by Kim Griggs 27 April 2005, BBC NEWS

For most people, the thought of hiking through cold, boggy tracks to sleep in a small tent on a steep hillside, and then to be woken four to fives times a night, doesn't sound like a holiday.

But that's how volunteers looking after the nests of New Zealand's kakapo have spent two weeks of their summer holidays this year.

The critically endangered kakapo - fat, green, musty-smelling nocturnal parrots, which cannot fly but can climb tall trees - are confined to New Zealand's offshore islands.

Kakapo ( Strigops habroptilus ) numbers dwindled to just 51 in the mid-1990s, but an intensive conservation effort has boosted their numbers.

This year, on the predator-free Codfish Island/Whenua Hou, off the bottom tip of New Zealand, a team of volunteers and Department of Conservation (DOC) staff have watched over five new chicks.

"The people that we want, who are interested in conservation, they usually seek us out," Vivienne Parker, who organises the volunteers for DOC's kakapo team, told the BBC News website.

"All the volunteers we've had have been absolutely amazing. Just incredible."

Night watch

Each night, nest-minders camp in a tent near a nest. Their job is to monitor the egg or chick whenever the mother leaves the nest, moving in with special heat pads to help the egg or chick stay warm.

"Nest-minders get woken up at all hours... from seven o'clock in the evening, right through to four o'clock, six o'clock in the morning," explains Tony Preston, a member of DOC's kakapo team.

DOC also uses volunteers to trek around the island to provide the nesting birds with supplementary food. Another volunteer cooks the meals for the 15 or so people on the island during a breeding season.

Ben Machin, an automotive engineer from Dorset in England, has found it wasn't so much waking up that was the problem during his nest-minding stint.

"It's more your nerves that you have to get over," he says. "You go up there a couple of nights with somebody who is a veteran and they make sure everything is good, which gets you over your first time. It becomes second nature really after that."

Taking the food to the birds' feeding stations is less nerve-wracking but it involves a lot of walking, and an hour or so of preparation, as the food for each kakapo is weighed individually.

"Each bird has different amounts depending on how much they eat and whether they forage for themselves [or] whether they are supporting chicks," Mr Machin said.

"We put [the food] into little hoppers. We clean up the water. We check for any mould, and bring back any food that they have left so we can judge how much they have eaten."

It takes the three volunteers who feed about an hour-and-half to organise the food. Then they each have to trek around the island to the feeding stations.

"The walk, depending how fast you want to go, takes anywhere from three-and-half to six [hours]. Six is if you take it real slow taking in some scenery," said Mr Machin.

Lonely outpost

For those not quite so keen on all the walking involved, the other volunteer role is that of cook. It's a role New Zealander Rennie Gould has taken on with aplomb. "I'm not terribly fit so I decided to be cook rather than nest-minder. I'm really glad I did; it's been great," she said.

For her, coming to help with the kakapo gives her a break from the intensity of her work as a criminal defence lawyer. And the deaths last year of three young female kakapo hit home with Gould. "When they lost three, I just really wanted to do something."

Nest-minding for the five kakapo chicks on the island has finished for this season, but volunteers will be continuing to feed the kakapo during the rest of the year.

And in coming antipodean summers, nest-minders will again be needed, as the Department of Conservation aims to lift the female kakapo population from 38 to 55.

And while Codfish Island/Whenua Hou may not match up to the usual vision of an island holiday - accommodation is in bunkrooms, the toilet has been dug into the ground and cell phone reception can mean a hike up a hill - it is unique.

Ben Machin said: "You're on an island where you can't come unless you are working for DOC. An absolutely unspoilt island."

fearful dream of something like a bird or dinosaur

how they loved their falcons

Tuesday, April 26, 2005

A package arrives

I feared the worst, expecting the Mummy’s hand or something equally disgusting, I guess, as the paranoia is getting deep around here these days, with the elevated terrorist threat levels and increased security. I was shocked that the package had gotten through Security into the residential compound.

Inside the box lay a museum-quality hand-held computer-telephone mash-up, circa 2007 (but I’m no expert). Narrow enough to slip into my shirt pocket, the length of the checkbooks they used to use back then, before bank cards got smart.

I flipped open the brushed aluminum case. I expected it to power up; it did.

But, instead of the telephone call that I expected, from some Mysterious Stranger who is Going to Change My Life...the device logged itself on to a computer server somewhere, a direct connection, not through the public net.

ASCII gibberish scrambled the screen for 63 seconds before the following message appeared:

Welcome, Redactor!

That was a shocker. The only place I’ve used that name is in this journal, nowhere else. And this journal is private. Or so I thought. My gut began to tighten.

You’re not going to find what you’re looking for in the servers you have access to, Redactor.

The screen offered a text box where I could enter a response and tapped the keyboard for a moment.

Who are you? I typed.

Check this out. I’ll get back to you later.

The screen went blank as the email clicked off. A few moments passed.

The screen burst to life with chimes playing the melody from the eternal "Stairway to Heaven."

An email message opened.

Don't even think of telling anybody about this, if you know what's good for you.

Hmmm.

Threat? I typed.

Reality, I'm afraid. OK, later.

The screen scrambled then went blank as it began another download.

Through the window I watched half a dozen outraged mockingbirds dive-bomb a huge raven perched on the decapitated fir tree in the widow lady's yard across the street. The raven puffed out its chest and talked back to the mockingbirds who continued to scream as they swooped perilously close to the corvid's hooked black beak. The raven fled south on Downey, mocks in hot pursuit. Seems to be a nest they were protecting in that fir tree, as there is in the tree out at the curb, visible from my office window here, a tree whose name I, lamentably, do not know, bursting this week into hot pink blossom.

raptorvision

The task is to document every reference in the mediasphere, as well as gather relevant names and contact information when possible, for people who are involved in publishing or otherwise disseminating falcon or falconry references.

Learning about these birds has been a delight. Their eyes, for example:

The power of sight is of paramount importance to birds-of-prey, all of which have forward sight with overlapping 'binocular' fields of vision. Acuteness of sight is difficult to define but if we were endowed with the eyesight of a kestrel it is estimated that we could read a newspaper at a range of 25 yards. Better still, if we had the vision of an eagle we would be able to detect the twitch of a rabbit from a distance of two miles.

One explanation for hunting birds' phenomenal eyesight is the sheer size of the retina. This is the screen at the back of the eye on to which the lens casts an image. Compared to ours, an eagle's retina is physically larger. The retina is composed of rods and cones, two different kinds of light-sensitive elements. Rods register shape, whereas cones discern colour. The retina of a human eye contains 200,000 rods. An eagle has about a million. However, you ain't seen nothing yet.

In 1995 the mind-boggling discovery was made by Finnish researchers that some birds-of-prey see a wider colour spectrum than we do: including ultraviolet light. How might this be useful? Kestrels are a familiar sight hovering along motorway verges and grassland. They are watching for small rodents. Their quarry is fast and nimble and ranges over habitat that is often uniform and extensive. At times, the kestrel's task must seem like a search for the proverbial needle in a haystack. However, rodents mark their runs with urine and faeces, which are visible in ultraviolet light. In tests, wild kestrels brought into captivity were able to detect vole and mouse latrine scents in ultraviolet settings. This ability enables them to screen large areas of vegetation in a relatively short time and to concentrate hunting at 'busy intersections.'[61]

This brings to mind the familiar ChurchØne® teaching on the eyesight of the Eagle, how it equates to vision in terms of insight, knowledge, and wisdom. Every Fledgling knows that vision, plus superior size, makes the eagle a predator of the falcon.

peregrine egg spared student scramble

by Ashley Bach

Seattle Times, April 26, 2005

Booth Haley speaks in exclamations and explains his yolk-related legal problems with a certain flair, including diatribes about living off the land and society's reliance on store-bought food.

The 22-year-old Haley is from Mercer Island, attended Mercer Island High School and is about four weeks from graduation at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Conn. He was arrested April 7 for taking a special kind of egg from a nest sitting on a railroad bridge near campus.

To hear him tell the story, he was just a college student in search of a unique meal. To hear state environmental officials tell it, Haley was endangering a rare species, and maybe worse.

Haley was canoeing with a friend on the Connecticut River when the two men came across a metal ladder rising from the water. They decided to climb about 80 feet to the bridge, where they saw a nest sitting on the edge of an old iron control booth.

Inside were four small eggs, dappled brown, and Haley, a longtime climber and outdoorsman, decided to take one. To eat. "Probably scrambled," he said.

But a state conservation officer happened to be in the area and witnessed the grab. Haley and his friend were arrested and charged by Middletown prosecutors with third-degree trespassing, a misdemeanor, for walking on the bridge.

And the egg, it turns out, was from a peregrine falcon, an endangered species in Connecticut, state officials said. Only six pairs exist in the entire state, including those nesting on the bridge.

The two men could face up to three months in jail on the trespassing charge, and state officials are considering charges related to the egg pilfering. Federal officials are trying to determine if Haley planned to sell the egg on the black market.

Haley, described by friends and family as "mischievous," "careless" and "unusual," but no egg trafficker, says he was just hungry. He has been a longtime proponent of finding food in the wild, from oysters to snails, and the egg was something new.

"I thought, 'Wow, what a great opportunity! I'd like to try one and see what it tastes like,' " he said.

Haley said he thought the egg was from a pigeon or seagull, and his only question was whether the mother bird would mind the missing egg.

Connecticut wildlife officials aren't sympathetic. They understand how young people can sometimes do crazy things, but messing with the peregrine falcon is altogether different, said Dwayne Gardner, spokesman for the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection.

"Mischief is mischief, but when it threatens an ... endangered species, we have to take it seriously," Gardner said.

It is illegal in the state to take eggs from any wild bird, Gardner said.

Wildlife officials returned the egg to the nest, and it is developing normally, Gardner said.

Haley's friends have started a Web site in his defense (freebooth.org). They sell T-shirts with Haley's head coming out of an egg, reading, "Free Booth!" The site's front page says Haley faces criminal charges "for basically just being an idiot."

"It was a foolish mistake with consequences far greater than the actions deserved," said Ben Rogovy of Seattle, Haley's childhood friend.

Haley said he regrets taking an egg from a rare bird, but not the act of taking an egg in general.

The arrest generated a lot of media interest in Connecticut, and Haley still hears comments about it.

"Anyone who knows me has come to expect these playful adventures," he said, "and they think this is not at all out of character."

But, he added, "People who don't know me think I'm crazy."

falconcam

From the Indianapolis Star [5]:

A winged drama is unfolding 31 stories above the sidewalk, and everyone is invited to peek in from time to time.

A pair of peregrine falcons are watching over three to four eggs in a nest on Market Tower Building at Market and Illinois streets, and the progress of this high-flying family can be monitored by Falcon Cam and a Web log that are providing periodic updates.

photo: Indianapolis Star

Stormy weather ahead

It's a Jungle Out There!

Stormy weather ahead, warns a University of Oregon geologist [4]:

"We know the gathering greenhouse will be warm, but this new information confirms that the contrast between the rainy season and the dry season will increase dramatically," says Greg Retallack, whose study indicating that a troubled greenhouse is brewing is published in the April issue of the journal Geology.

Wardrobe opportunity! Bikini. Miniskirt. Beach and resort ware....

....some 55 million years ago during the late Paleocene epoch....Wyoming warmed from a mean annual temperature of some 55 degrees to a summer-like 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Rainfall in Utah jumped from 16 inches per year to 26 inches per year. As a result, sagebrush deserts of the western U.S. were transformed into sub-humid woodlands.

And that’s a problem because...?

Retallack agrees with previous research indicating that the cause of the late Paleocene greenhouse spike, which lasted less than half a million years, was a catastrophic release of natural gas from undersea ices and permafrost.

"In a remarkable parallel to modern hydrocarbon pollution of the atmosphere, this natural methane oxidized to carbon dioxide and created a global greenhouse event," he explains. "The past methane outburst dwarfed even human consumption of hydrocarbons, and there is a danger that another similar outburst could be triggered by warming of polar and submarine ice due to human activities. Our little warming push could repeat the troubled times of 55 million years ago."

...."During the greenhouse spike of 55 million years ago, tropical mangroves and rain forests spread as far north as England and Belgium and as far south as Tasmania and New Zealand," Retallack says. "Turtles, alligators and palm trees graced Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic, which is now the treeless abode of musk oxen and polar bears."

The bottom line? A new Ice Age is probably the least of our worries.

The desert blooms! If that’s the case, bring on the greenhouse gas!

"Frostbite and snow-blindness are less likely to be in our future than heat stroke and malaria," Retallack asserts. "Mint julep, anyone?"

Make mine a double. After all, "It's a Jungle Out There!"

Unscrambling the titanosaur omelette

What's really surprising is how little difference there is between the programming of 2005 and the stuff they're doing today. The preoccupation with Mother Nature in all her exotic manisfestations, oddities, freaks, and her undeniable dangers and pitfalls, fear-mongers...

It's a Jungle Out There!

Dinosaurs were just overgrown chickens!

That’s the startling conclusion announced [1] by scientists who recently compared protein in chicken eggs to eggs of the titanosaur, a humongous, giraffe-necked plant-eater that roamed the wilds of Patagonia some 70 million years ago.

After sequencing the amino acids of the ancient proteins, the titanosaur DNA will be used to improve current poultry and reptile breeding stocks by increasing meat yield and nutritional value.

We'll need all the strength we can get to defend ourselves from swarms from the south. Bees, I mean, not infiltrators from the Caliphate.

This just in: Assume any bee you see is Africanized and dangerous, warns Exterminator Doug [2].

Killer bee

But, these bees are the least of our worries, judging from this lovely encounter, from the Guardian [3]:

....residents of the blossom-filled streets of Sydenham were still shaking last night as a father of three told how he had been mauled by a black cat the size of a labrador.

Police armed with Taser stun guns sealed off roads in south-east London, school gates were locked and teachers warned pupils to keep away from wooded areas after Tony Holder escaped with a cuff around the face from the big cat.

Mr Holder, 36, was calling in his tabby, KitKat, at 2.15am yesterday when he spotted his pet being savaged by a 5ft-long animal.

The black, panther-like creature then sprang at him in his back garden.

"It had pinned the cat down, but when it saw me it let the cat go and jumped on my chest, knocking me to the ground," he said.

"I could see these huge teeth and the whites of its eyes just inches from my face. It was snarling and growling and I really believed it was trying to do some serious damage.

"I tried to get it off but I couldn't move it, it was heavier than me.

"I was scared. I really thought my life was in danger but all I was worried about was my family. It was an absolute nightmare."

In the gloom, Mr Holder's 11-year-old daughter Ashleigh, watched from a bedroom window. I just saw my dad flying backwards and struggling with something," she said. "I was really scared."

As Mr Holder was being treated for scratches by ambulance staff, he saw the beast saunter past again.

Armed police arrived, sealed off the streets around Mr Holder's home, loaded their stun guns with tranquillisers and searched for it with flashlights.

The animal gave them the slip, but as tabloid reporters scoured the streets in safari gear brandishing butterfly nets, the Guardian picked up the scent of something big across the railway line by Catling Close.

Billy Rich, 44, was looking out of his window at 5.30am when he saw a black creature leap across the road and bound south towards Mayow Park.

"I see a ... thing," he said.

"What's he supposed to have seen?" asked his ex-wife.

"The beast of Sydenham," your correspondent explained.

"The only beast of Sydenham is him," she replied, prodding a finger at Mr Rich.

"On the news they said it was as big as a Doberman, but it wasn't," insisted Mr Rich. "It was big and black and I thought, fucking hell, what was that?

"It definitely wasn't a pussy cat. It was too big. The way it jumped, you could tell it wasn't a dog. It definitely wasn't a fox, but it can't be a panther - where would a panther come from in Sydenham?"

The British Big Cat Society estimates there could be 100 big cats roaming the land. A £5,000 reward has been offered for the Beast of Burford, a large black cat spotted near the Oxfordshire town.

Scotland Yard confirmed the beast of Sydenham was the second serious sighting of a large black cat in south-east London in the past three years.

Officers responded to reports of a large black cat in Oxleas Wood in Shooters Hill, south London, in 2002 but failed to trace the animal.

Danny Bamping, the founder of the society, warned that if the cat was a melanistic leopard or a black panther, it could kill. "They can be very, very dangerous," he said. "There have been incidents in North America where joggers have been killed by these creatures."

A Scotland Yard spokesman confirmed that officers had visited schools to warn them about the big cat. "A police officer who attended the incident said he thought he saw what looked like a black labrador," the spokesman said.

One pupil at Sydenham high school for girls said the gates had been locked at lunchtime and students had been told to stay away from wooded areas and dark alleyways.

She said they had also been instructed to make a loud noise wherever they went to scare off the beast.

Parents said they would be keeping their children indoors. "The garden is secure but I wouldn't let my little boy Morgan go out and play today," said Kelly Wood.

"He's 19 months. I think he's quite an edible size."

Quite.

Don't forget, "It's a Jungle Out There!"

falconspace?

Among other duties, I find, catalog, and, as necessary, restore information resources pertaining to certain actors in the crisis that almost destroyed the Congregation in the first decade of the present century. The Elders are especially interested in the leaders of the rebel campaign of 2005. I've spent half a century tracking mediasphere references to the handful of rebel leaders who survived the suppression of that movement in 2007, and the continuing disssemination of the ideas and literature that inspired their revolt.

I also track references to falcons, falconry, ancient falcon worship, part of the larger CR collection regarding raptors generally and eagles specifically, which is the primary focus of the CR praycirc in which I co-create, collaborate, and congregate in the course of my sacred work assignment.

I don't perch high enough in the ChurchØne® pecking order to enjoy the privilege of practicing falconry – that's reserved for the highest circle of Elders, plus technical staff who work directly in the raptor restoration and conservation programs. But, vicariously at least, I've grown strangely fascinated with this ancient sport, and love watching the various hawks and falcons that live here in St. Hubert and Sanctuary nearby.

In this blog (I borrow the term from the turn of the century, a contraction of "web log" taken to mean public journals published by individuals on the Web, although this journal is, I hope - I have taken not-inconsiderable pains to make it so - private and secure), I archive items, related to my official duties, mostly found in the turn-of-the-century servers I mine, culled largely from the mainstream business, academic, and entertainment media (especially the extraordinarily long-lived It's A Jungle Out There! mediasphere franchise which has been publishing in one format or another - print, radio, television, online, satellite, telephone, etc. - for nearly two centuries now), and other private research...including certain documents and transcripts yet unpublished, which, perhaps unsuprisingly, tell a story radically at odds with ChurchØne® Doctrine...

Monday, April 25, 2005

macaque mystery mitigated

Gibraltar macaque

DNA solves mystery of Gibraltar's macaques

CHICAGO--After decades of speculation, the origin of Gibraltar's famous Barbary macaques has been determined.

The only free-ranging monkeys in all of Europe, Gibraltar's 200 or so semi-wild macaques enjoy the run of the hillsides in this British territory – much to the delight of millions of tourists, as well as to the chagrin of some officials responsible for their management.

There were not always, however, this many macaques on Gibraltar, which serves as a gateway to the Mediterranean Sea. In 1942, after the population dwindled to almost nothing, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered that their numbers be replenished due to a traditional belief that Britain would lose Gibraltar if the macaques there ever died out.

The clandestine move was taken to bolster Britain's morale during World War II. Ever since, scientists have wondered exactly where the macaques came from.

Now, an analysis of mitochondrial DNA from 280 individual samples reveals that the macaques on Gibraltar descended from founders taken from forest fragments in both Morocco and Algeria. The embargoed research will be published in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (http://www.pnas.org/papbyrecent.shtml) on April 25, 2005. It will appear subsequently in PNAS' print version at a date yet to be determined.

"Our project was designed as a test case for conservation genetics," said Robert D. Martin, a primatologist, Field Museum Provost, and co-author of the study. "The Gibraltar colony of Barbary macaques provided an ideal example of genetic isolation of a small population, which is now a regular occurrence among wild primate populations because of forest fragmentation. To our surprise, we found a relatively high level of genetic variability in the Gibraltar macaques. This is now explained by our conclusion that the population was founded with individuals from two genetically distinct populations in Algeria and Morocco."

Key to study: mitochondrial DNA

In mammals, mitochondrial DNA is inherited exclusively from the female, so it can be analyzed to determine matrilineal origins. This is especially relevant with mammals, such as macaques, that practice female philopatry, a social system in which females remain in their birth groups while males migrate between groups.

The research first identified 24 different haplotypes in the Algerian and Moroccan colonies of macaques. Each mitochondrial haplotype is identified by means of a specific DNA sequence.

Since the Algerian and Moroccan haplotypes are clearly distinct, evidence of any given haplotype in the mitochondrial DNA of Gibraltar macaques would indicate that they descended from the geographical population with that haplotype. It had long been thought that the Gibraltar macaques were exclusively derived from founders imported from Morocco. In fact, both Algerian and Moroccan haplotypes were found among the Gibraltar macaques, indicating that the Gibraltar colony was founded by female macaques from both regions.

There are 19 species of macaques, which have proven to be remarkably adaptable. In fact, macaques are found in more climates and habitats than any other primate except, of course, humans.

The Barbary macaque, M. sylvanus, is the only species that lives naturally in Africa; all other species live in Asia. Some scientists believe the Barbary macaques were first brought to Gibraltar by the Moors, who occupied Spain between 711 and 1492. On the other hand, it's possible that the original Gibraltar macaques were a remnant of populations that had spread throughout Southern Europe during the Pliocene, up to 5.5 million years ago.

About 20 years ago, scientists estimated there were 20,000 Barbary macaques in Africa. Today, the wild population is only half that number, which led the World Conservation Union in 2002 to include the Barbary macaque as "vulnerable" on its Red List of Threatened Species.

The research also indicated that the initial split between two main subgroups of M. sylvanus occurred about 1.6 million years ago. The other co-authors of the study are Lara Modolo at the Anthropological Institute of the University of Zurich in Switzerland, who conducted all of the laboratory work on the DNA samples, and Walter Salzburger at the University of Konstanz in Germany.

"Our findings reveal that the Algerian and Moroccan populations are genetically very distinct and that there are major genetic differences even within Algeria," Modolo said. "Mixing of founders from Algeria and Morocco explains why the Gibraltar macaques have kept a surprisingly high level of genetic variability despite a long period of isolation.

"At the same time, the large degree of genetic difference seen between various wild populations tells us that we should be cautious about translocating animals from one area to another," she added. "This is just one of the lessons for conservation biology to be learned from this study."